Abstract: Improving levels of walking and cycling is critically important for the nation’s health and wealth. This article explores the reasons why focusing on working with children and schools to enable cycling in particular is likely to yield the best results for mode shift, by looking at behaviour change models as well as what is known about human travel behaviour.

Background:

It is critically important that we allow more people to choose to travel by walking and cycling. This is for a number of reasons:

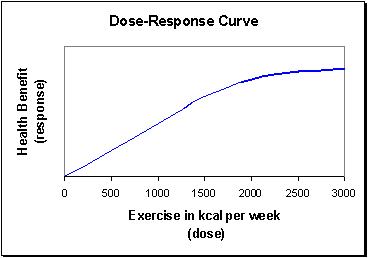

- Inactivity is having a massive adverse impact on health

- It is likely that humans need far more exercise for optimum health than was previously thought – far more than is likely practical for most to fit into their lives without a large component of this exercise being achieved through using transport time

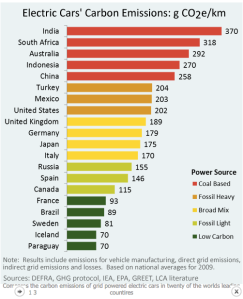

- Air pollution is one of the big killers and primarily associated with motor travel

- Motor travel is hugely expensive to the state above and beyond income from taxes on motoring

More walking and cycling tackles all of these issues at once. Walking and cycling are also, fairly uniquely, in both the individual’s interest to participate in (saving money, faster travel, better health) and in the Government’s interest for individuals to participate in (reduced expenditure, improved population health, greater productivity from the population).

Why focus on cycling?

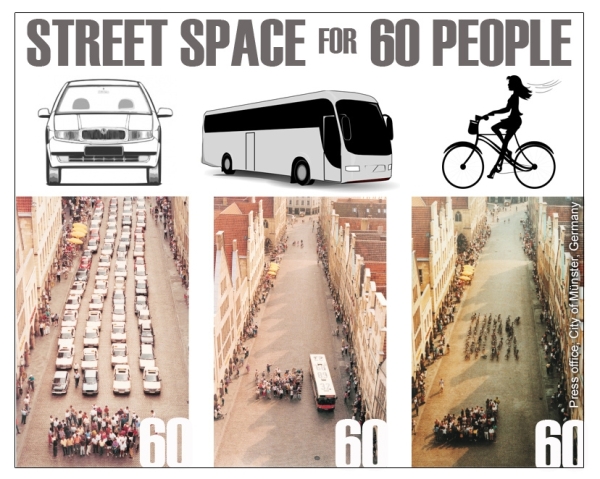

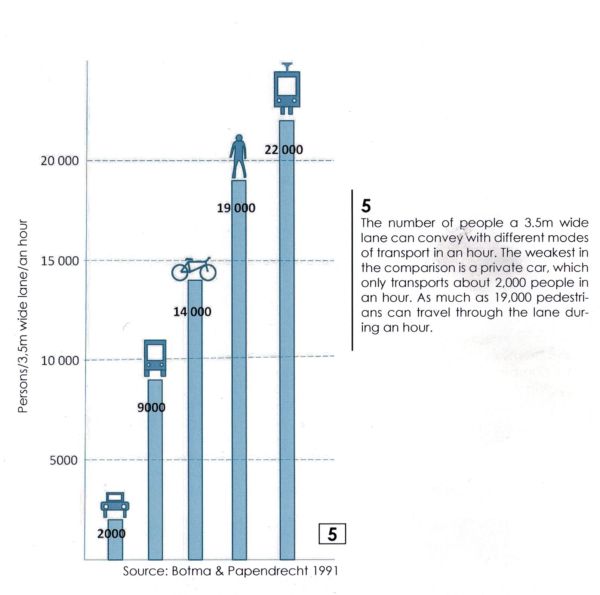

Looking at the walking environment in the UK, it is clear that walking is an accessible option for many, at least for short journeys – although there are problems caused by the volumes of motor traffic (i.e. crossing times, noise and pollution making for an unpleasant walking environment). Cycling, on the other hand, provides a viable option for many more journeys by allowing for greater distances to be covered; shorter journey times and larger carrying capacity.

But cycling is not currently viewed as a viable mode of transport by many; mainly due to fear of motor traffic associated with lack of fit-for-purpose provision for cycling. It is my view that in general, the things which facilitate cycling also help to reduce motor traffic volumes, therefore improving the walkability of an area in the long run. The same argument applies to good public transport – however, this is provided at much greater expense to the state. We should therefore be prioritising cycling as the area for greatest potential gains.

It is clear that one of the features that stands out about cycling cultures is that there is a great emphasis on allowing and encouraging children to cycle. In the Netherlands, the Fietserbond (Cyclists’ Union) go into schools to deliver cycle skills training, and new schools are designed in such a way that they are away from roads; encouraging walking and cycling. The Danish Cycling Embassy are keen to focus on the importance of encouraging children to cycle.

Overcome the barriers to entry early

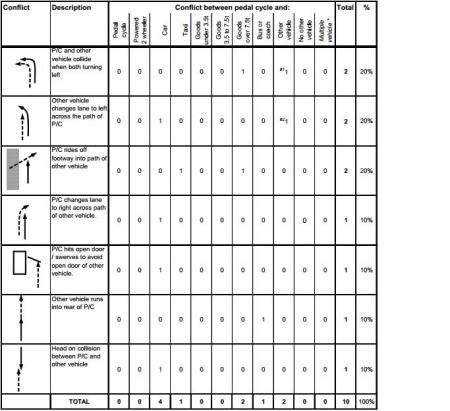

Beyond the immediate environment, there are a number of skill and knowledge based barriers to cycling. Potential utility bike riders need to know: how to ride a bike; where to go to get bike repairs; where to go to buy a bike; what sort of bike is likely to be practical for them; how to plan routes to where they want to go; how to manage traffic whilst riding (even in the Netherlands, cyclists must mix with low levels of low speed traffic on occasion); how to carry a passenger; how to secure a bike so that it won’t get stolen.

Helping children overcome these barriers means that not only are they more likely to be able to cycle as children – but they will turn into adults with cycling as a practical choice, without these barriers to overcome.

Humans are habit-forming creatures

The reason why there is sometimes a gap between what seems rational in terms of behaviour and what we actually do, is habit. It seems likely to me that as decision making is hard, and uses limited resources, humans tend to use strategies to minimise the need for this.

Habit or routine is one such strategy. Rather than re-think every single decision every single day, we take a decision once, and then just re-use that decision. I think this is why we find starting a new job, a new school, or even using a new mode of transport so exhausting – because we’re having to make many ‘new decisions’.

Some people take habit to extremes – for example, Mark Zuckerberg buys multiples of the same clothes, and generally wears the same outfit every day to minimise energy spent on ‘frivolous’ decisions. I’m not sure this is rational for everyone however, as appearances do count for most of us, most of the time – this might be especially true if you’re from a poorer background.

If we are minimising new choices, then it is logical to think that we will use modes of transport that we are most familiar with. This is borne out by what we see in travel choices of individuals, with previous travel behaviours often carried forward when circumstances change. For example, immigrants living in the Netherlands are more likely to cycle than people in their home country, but still significantly less likely to cycle than those born in the Netherlands.

My personal experience bears this out (anecdote alert!) – on moving from the country where driving had quite a lot going for it, to London where it didn’t, I continued driving for most journeys until a budgetary crisis forced a rethink and ‘eureka’ moment of realising that cycling was, for me as someone who had learned to cycle on the road as a child, much faster and much more efficient than driving as well as saving me a shed-load of cash and allowing him to go on holidays again (even if recently these ‘holidays’ mostly ended up turning into field trips exploring and trying to understand what has underpinned development of cycling cultures in places such as the Netherlands, Denmark, parts of Switzerland, parts of the US etc…).

Making sure that children have a habit of cycling for at least some of their journeys, then, is likely to lead a higher adult cycling population. It should be noted I am saying ‘this is likely’ because it is surprisingly difficult to find direct, thorough research on this effect – please do comment below if you manage to find any!

Parents and carers are likely to be more open to changing travel behaviour than other adults

Working with children doesn’t just benefit the children themselves. Children have parents, and often a network of carers (family and friends) who also have an incentive to want to join in with cycling that the children may be doing – if the child is enjoying something, they want to be part of that. Not only this, but behaviour change models suggest that we tend to be most open to changing our behaviour when we change something in our routines. Children are constantly changing routines, and causing change in their carer’s routines too – changing schools, a new after-school club, all these result in carers having to re-think their travel routines. These continual transition states provide a great opportunity to get the carers involved in cycling too.

Best practise design for allowing kids to cycle is best practise for everyone

Children have smaller legs than adults and therefore have the greatest need for direct routes that minimise gradients and stopping; they also have the greatest need for both subjective and objective safety, with forgiving design allowing for mistakes. These attributes are also the attributes that make for the most attractive cycling routes for adults too – faster routes that feel, and are, safe.

Summary

Working to enable more children to cycle not only has huge benefits for children directly empowered to cycle, but also has a disproportionate benefit in terms of enabling more travel by bike in general. The children directly empowered are likely to choose cycling as a mode choice throughout their life (ie 60-70 years of benefit from the behaviour change effort), but they are also likely to encourage parents and carers, who are more likely than other adults to reconsider their travel options and therefore take up cycling.

Conflict of interest statement: I work in local authorities on a range of projects which are all at least partly aimed at allowing children to use bikes for useful journeys.